Editor’s note: This post is part of a weekly, year-long series called the Nourishing Effect. It explores how hunger affects health through the lens of the 2016 Hunger Report. The Hunger Report is an annual publication of Bread for the World Institute.

By Bread for the World Institute Staff

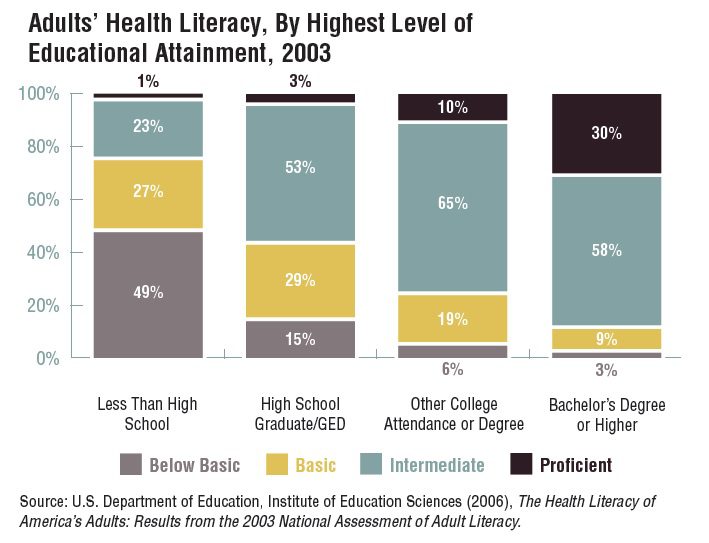

The most consistent predictor an adult will die in any given year is his or her level of education. In medical jargon, education is a “social determinant of health.” Health literacy, as defined by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, “is the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process and understand basic health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions and adhere to sometimes complex disease management protocols.” Virtually every encounter with the healthcare system is a test of a person’s health literacy skills, and health literacy is directly related to educational outcomes. In turn, educational outcomes are linked to the quality of schools one attended, and the quality of schools to socioeconomic conditions.

Nearly half of adults surveyed with less than a high school education have “below basic” levels of health literacy. A parent without a high school degree is statistically more at risk of raising a child in a hungry household than a parent who finished high school. Without a degree the parent earns lower wages and faces longer spells of unemployment. This means that the family’s housing options are limited, their neighborhood is less safe, and the increased stress caused by living under these conditions often creates strife at home. Hunger undermines a child’s ability to learn. Falling further behind with each hungry year, the child drops out like mom or dad. Now there are two generations with limited capacity to follow medical instructions.

Today, public health is concerned with the factors that perpetuate population health inequities. “Where people live, work, learn, and play has a greater influence on their health than what goes on in the doctor’s office, yet the healthcare system bears the brunt of these problems when they ultimately lead to poor health outcomes.” This statement appears in a 2015 report, A Prevention Prescription for Improving Health and Health Care in America, written by a taskforce of health experts under the aegis of the Bipartisan Policy Center. Their overarching recommendation is telegraphed right there in the title of the report: Invest in prevention.

Time and again research has confirmed the age-old maxim that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Prevention strategies take place “upstream” and affect the social determinants of health. Public health departments and the social service providers they partner with work upstream. Medical care is “downstream.” By the time a person with a chronic illness arrives downstream, damage control is the best doctors can do. They may have little to offer but efforts to slow down the progression of a disease.

Health care in the United States has been labeled a “sick care system,” overemphasizing treatment at the expense of prevention. This is reflected in the tiny fraction of government health spending that is dedicated to public health activities—in 2012, only 2.7 percent of federal and state health spending combined. Health literacy is one of those activities that, with more robust investment, can have a profound impact on improving population health upstream to lower healthcare costs downstream.

This text originally appeared in the Introduction of the 2016 Hunger Report: The Nourishing Effect. Read the full report and find references for the information shared above.