Editor’s note: Bread Blog is running a weekly, year-long series called the Nourishing Effect. It will explore how hunger affects health through the lens of the 2016 Hunger Report. The report is an annual publication of Bread for the World Institute.

By Derek Schwabe

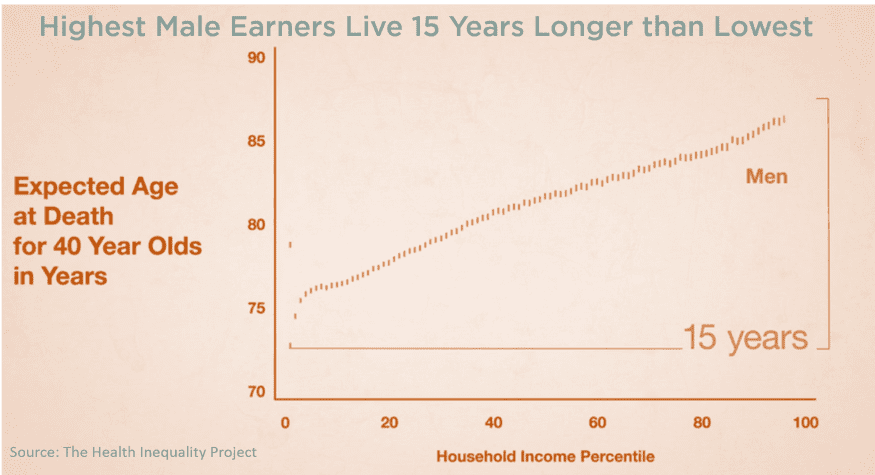

Life in poverty is often described by those who experience it as less of a life. Now, new evidence suggests that is quantifiably true. The poorest Americans do experience less of a life than the richest—about 10 to 15 years less.

Yesterday, a team of top economists released The Health Inequality Project, a comprehensive analysis of more than a decade’s worth of income and life expectancy data from tax and Social Security death records (stripped of identifying information). They found that men with incomes in the top 1 percent lived almost 15 years longer on average than those in the bottom 1 percent, while women in the highest income percentile lived almost 10 years longer than those in the lowest.

Interestingly, the study discovered that the breadth of the life-expectancy gap between rich and poor people varied greatly by location. Low-income people lived longer in more affluent cities that offer more robust services to needy families. For example, the poorest men in Detroit lived 6.5 years less, on average, than the poorest men in New York City. Among the poorest women in these cities, the difference was about five years. This underscores the important role of government programs in saving years of life that would otherwise be lost to income inequality.

Health behaviors such as smoking, sedentary lifestyle, and obesity also proved influential factors in life expectancy. Those with the highest incomes had more information and more flexibility to make choices that help people live longer. Low-income people are less likely to have the resources to invest in nutritious but costly foods such as fresh produce. People living in poverty have more difficulty avoiding damaging health habits such as smoking or eating highly processed food. And, as a recent blog post showed, hunger and poverty take a heavy toll on people’s mental health. Those impacted by poverty suffer toxic stress and are less able to advocate for better access to healthy foods and environments.

The Health Inequality Project isn’t the first study, or even the first this year, to estimate the amount of time that poverty steals from a person’s life, but, as one of the most thorough, the project uncovered data that led to substantially higher calculations of lost time.

Shorter lives are just one symptom of increasing income inequality – a problem that has gone unchallenged in the United States for decades. Health policy changes such as the Affordable Care Act have begun to push the U.S. healthcare system to do its part by paying more attention to prevention and root causes of illness. But undoing the damage caused by widening income inequality will take much more than that. Read the 2016 Hunger Report for concrete steps that policymakers can take to help reclaim the years lost to millions of low-income Americans.

Derek Schwabe is a research associate in Bread for the World Institute.