Editor’s note: This post is part of a weekly, year-long series called the Nourishing Effect. It explores how hunger affects health through the lens of the 2016 Hunger Report. The Hunger Report is an annual publication of Bread for the World Institute.

By Bread for the World Institute staff

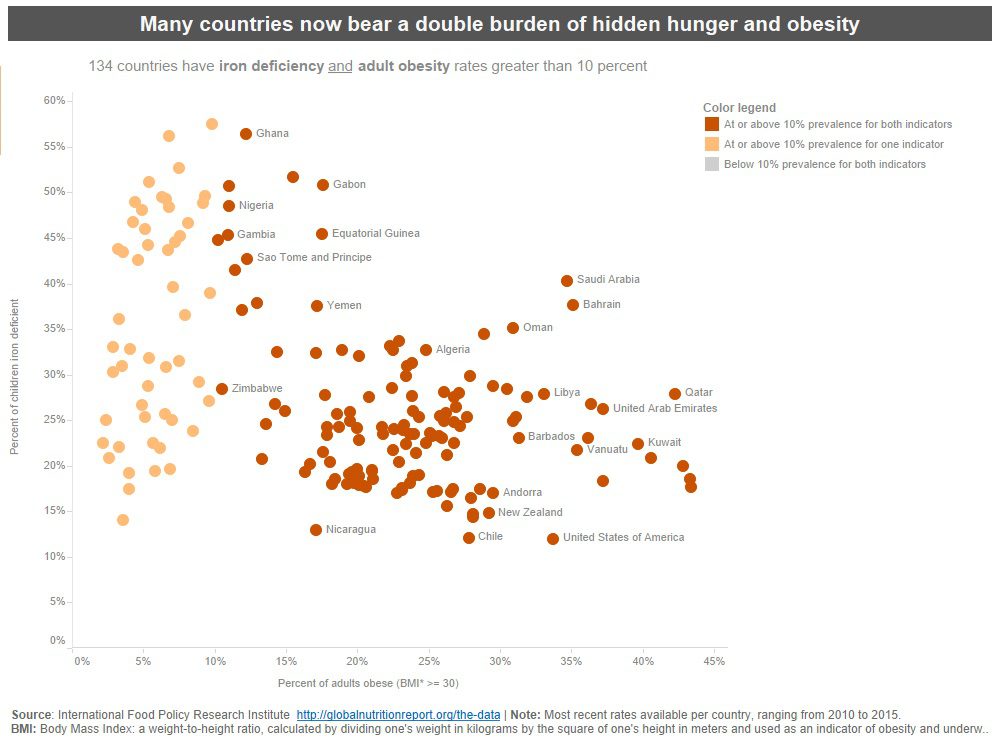

The fastest-growing form of malnutrition in developing countries is obesity. There are now more than twice as many people in the world who are obese as there are people who are hungry. The majority live in developing countries. See Figure 3.5. Rising obesity rates in developing countries could be considered a side effect of progress against poverty: obesity has risen in every part of the developing world where a large share of the population has escaped poverty. For example, in China, a country of 1.2 billion people, the Ministry of Health estimates that one in four people is currently obese. A national survey in 2013 found that 114 million adults (12 percent of the population) have diabetes, with an additional 493 million believed to be pre-diabetic.

One of the first lifestyle changes people make when they are no longer poor is in what they eat. As household incomes increase, families reduce their consumption of starchy staples and replace them with oils, fats, sugars, and animal products. This “dietary transition” is accompanied by what is sometimes referred to as an epidemiological transition: the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases, such as heart disease and stroke, catches up with, and then surpasses, the prevalence of communicable diseases. Sub-Saharan Africa is the only remaining region where communicable diseases claim more lives each year than noncommunicable diseases. Eighty percent of all deaths from noncommunicable diseases occur in low- and middle-income countries. The consequences of the “epidemiological transition” for families, communities, and economies are especially grave because in low- and middle-income countries, most death and disability from such diseases occur in working-age people (under 60).

In the early 1990s, physician and epidemiologist David Barker advanced an idea about the relationship between hunger and obesity that was at first considered controversial, but is now widely accepted by the medical establishment. The eponymous “Barker hypothesis,” also known as the “fetal programming hypothesis,” says that children of mothers who are undernourished during pregnancy and grow up in a postnatal environment of food scarcity are “programmed” to become obese in adulthood. If they make a dietary transition to oils, sugars, and animal products in adulthood, most will still not be able to afford the kinds of foods that promote good health. In South Africa, where four in 10 adults are obese, a family whose income is among the bottom third of national incomes would need to spend 30 percent more to achieve a “healthy diet.” But these families barely earn enough to meet minimum food needs.

To Barker, what should be done is neither complicated nor expensive. A child’s health at birth is most often a reflection of his or her mother’s health and nutritional status. It is fruitless to try to improve the health of a child while neglecting the mother; moreover, pregnancy is too late to truly break the cycle of intergenerational malnutrition. Thus, Barker said, “The greatest gift we could give the next generation is to improve the nutrition and growth of girls and young women.”

To learn more about the rising coexistence of obesity and undernutrition in poor countries, view our ‘Hidden Hunger’ data storytelling tool, and read Chapter 3 of the 2016 Hunger Report, The Nourishing Effect.