Editor’s note: The Hunger Reports is a more in-depth look at the 2017 Hunger Report, Fragile Environments, Resilient Communities, with a new video, blog series, and infographics. Blog posts offer glimpses into why hunger persists and what we can do about it.

By Michele Learner

The Sahara Desert, which already occupies 3.5 million square miles in Africa, is expanding due to climate change. The Sahel, the region that stretches across the continent to the desert’s south, is becoming more desert-like every year.

The Sahel, which includes parts of nine countries, has always been a difficult place to live and earn a living. Traditionally, most of its population has been nomadic, moving from place to place, accompanied by camels as well as livestock such as sheep and goats. Some groups have prospered, however, and the region has also supported thriving economies based on crisscrossing trade routes.

According to the United Nations, ordinary conditions in today’s Sahel region include millions of people living in a permanent state of food insecurity. Every year children die of malnutrition-related causes at rates well above the global threshold for a hunger emergency. When the 2005 famine in Niger made international headlines, many food security workers in the country questioned whether conditions were indeed much worse that year than in previous years.

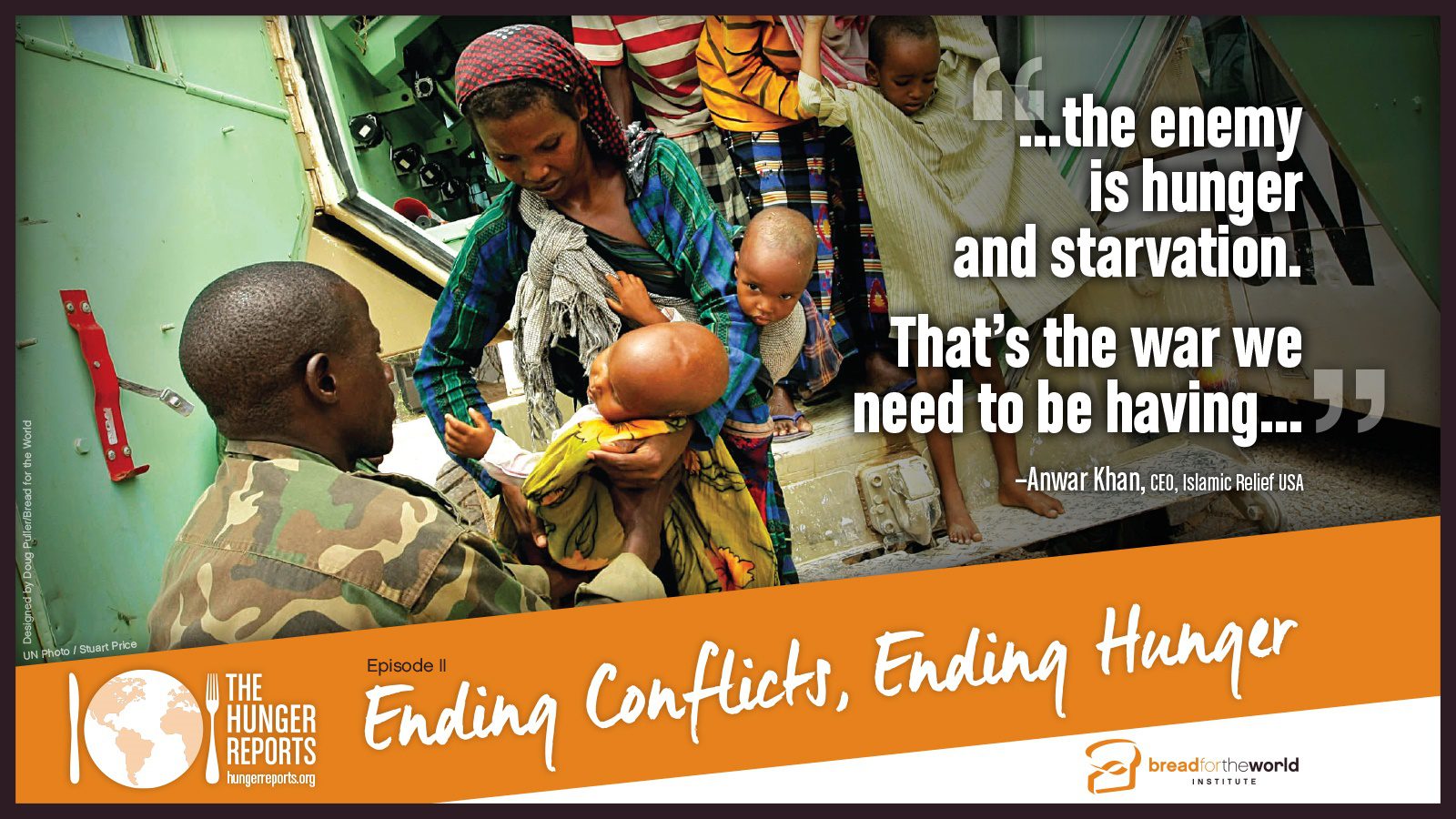

With an already challenging environment now affected by deeper and more frequent droughts, it is more and more difficult for people to eke out a living. Despite hard work, most families have few resources and options available to them as young children become lethargic from malnutrition, come down with illnesses that are dangerous given their weakened immune systems, and, all too often, die before their fifth birthdays.

Such profound economic vulnerability makes community-level development efforts far more difficult. It also makes younger people, in particular, more susceptible to the promises of extremist groups to provide their followers with a better life. As national governments continue to fight formal armed rebel groups, assorted jihadist groups have been contributing to the violence. Among these are ISIL and Al Qaeda in Mali, Boko Haram in Nigeria, and Al-Shabaab in Somalia.

Accounts such as this do not mince words: “Farmlands are invaded and looted by insurgents, farmers killed or kidnapped, markets bombed, farmers displaced as IDPs and refugees, animals seized, animal herding restricted, and farmland left uncultivated and not harvested.”

It’s not hard to see that armed conflict in an already hungry community further damages people’s hopes of keeping their children alive and well, much less working with others in their communities to build a stronger economy or find ways of adapting to climate change.

This is not to say that people in grim situations give up. They keep looking for solutions. Breaking the cycle could start with establishing social safety nets, particularly for women and children. This is one objective of the U.N. Integrated Strategy for the Sahel as it works toward enabling the people of the Sahel to build long-term resilience.

Food and nutritional security are at the center of the resilience strategy. Along with direct assistance for the most vulnerable, building this security could include, for example, improving irrigation and drainage, diversifying food sources, and finding better ways to store surplus food for the future.

But first, the fighting must stop.

Michele Learner is associate editor at Bread for the World Institute.