Editor’s note: This post is part of a weekly series on fragility and hunger, rooted in themes from the 2017 Hunger Report: Fragile Environments, Resilient Communities.

By Todd Post

Halting tropical deforestation is a low-cost and effective way to slow climate change. It also has the potential to deliver big benefits to those most at risk of hunger: rural poor people.

When forests are cleared, carbon dioxide stored in the soil and vegetation is released into the atmosphere, accounting for as much as 10 percent of total carbon emissions. That may sound small relative to overall emissions, but forests also remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, storing it in the soil and vegetation. Deforestation destroys the world’s safest and most natural form of carbon capture. Ending tropical deforestation and allowing forests to grow back could capture between 25 and 35 percent of carbon emissions from all other sources.

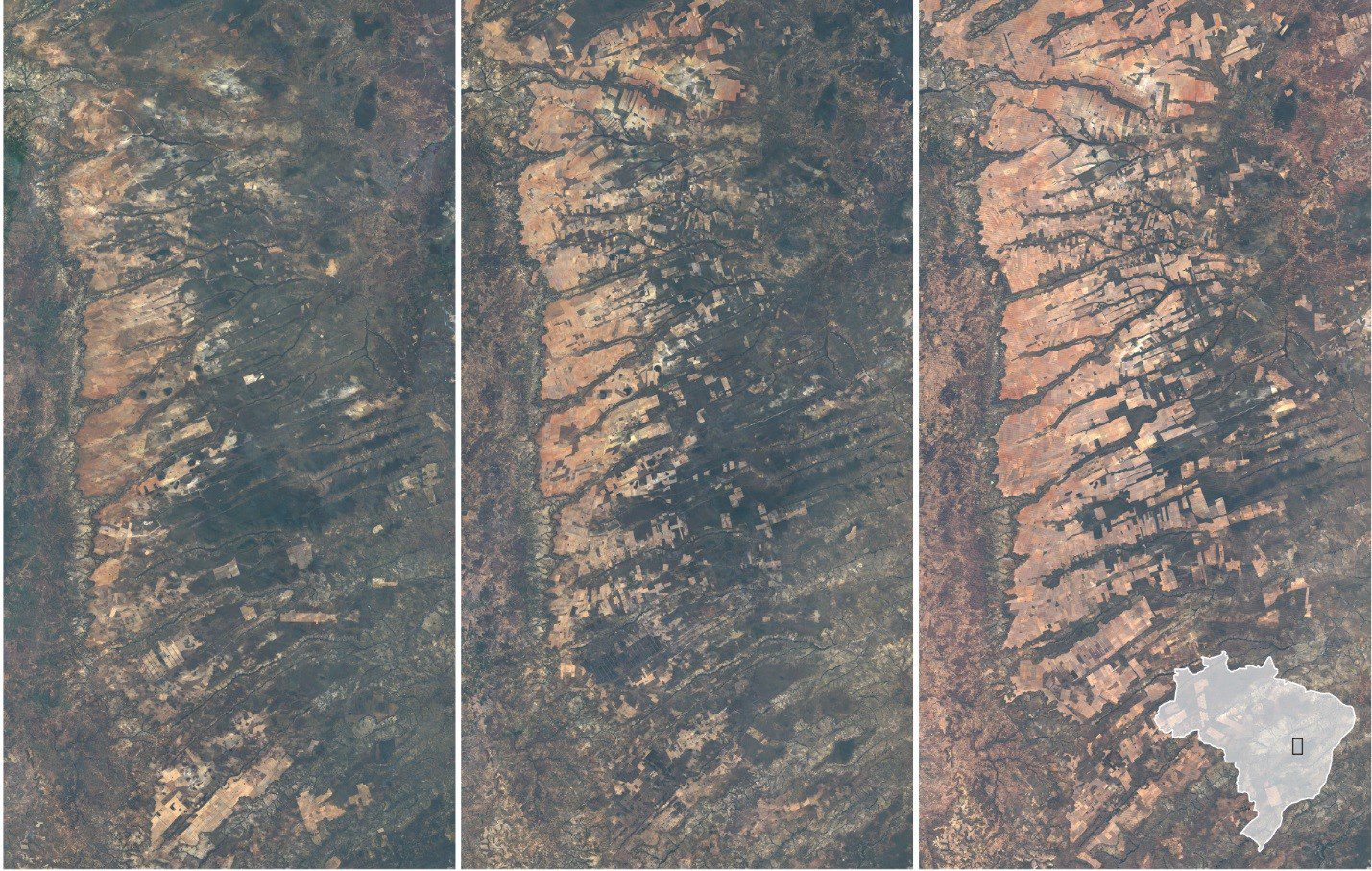

In 2010, developed countries agreed in principle to provide incentives to developing countries to reduce deforestation on a pay-for-performance basis. The initiative, Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation, or REDD+, is modeled on a bilateral agreement struck between Norway and Brazil, in which Norway provides development assistance to Brazil in exchange for Brazil’s reducing deforestation in the Amazon. Between 2004 and 2014, Brazil reduced Amazon deforestation by 75 percent, proving that making substantial reductions very quickly is possible. Results are easily verified with satellite imaging.

Payment-for-performance systems are designed so that donors essentially buy the outcomes they want, rather than paying for inputs, while the aid recipient gains the autonomy it wants to determine how those outcomes will be achieved. In the United States, the Center for Global Development is the most prominent champion of pay-for-performance systems, or what it calls Cash on Delivery (COD) aid, and has written extensively about how the REDD+ is ideally suited to a COD approach. “The key advantage of a COD approach,” says William Savedoff of the Center for Global Development, “is that it is consistent with our current understanding of how development happens: through domestic accountability, ownership, innovation, and adaptation. Recipients can still seek technical assistance and external ideas for their programs and policies, but the agreement itself does not constrain the recipient to follow preordained blueprints, which tend to interfere with real development and real progress.”

Developing countries certainly recognize that deforestation will make them more vulnerable to climate change. But here and now, food-insecure rural communities lack alternatives to cutting down trees for firewood or clearing hill slopes for food production. Rural households need to be compensated for lost income, and they will need complimentary supports such as fuel-efficient cook stoves, extension services so they can learn evergreen agriculture, and enhanced social protection programs. Brazil offers a monthly cash transfer to low-income households that commit to both zero deforestation and sending their kids to school. It has also instituted a process for granting land tenure to hundreds of thousands of indigenous smallholders, provided that they comply with regulations on deforestation.

Developed countries reiterated their support for REDD+ in the Paris Climate Agreement reached in December 2015 at COP 21. The Green Climate Fund is a mechanism for multilateral investments in programming oriented around REDD+ and is especially valuable to the United States. U.S. bilateral support for REDD+ is impeded by regulations limiting the provision of aid directly to governments. It is hard to envision having real impact on reducing tropical deforestation and not working directly with governments, as they have the capacity to work at the scale necessary to deliver significant reductions in deforestation in their countries.

Todd Post is the senior hunger report editor in Bread for the World Institute.

This story originally appeared on p. 86 of the 2017 Hunger Report: Fragile Environments, Resilient Communities.