By Michele Learner, Bread for the World Institute

Today, October 16, is World Food Day — celebrated on the date that the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) was founded. This year is FAO’s 70th anniversary, and the agency is spotlighting a hunger strategy that’s relatively new, successful, and rapidly expanding: social protection.

One of life’s most stressful situations is being unable to plan for the future. For people living in poverty in developing countries, there is very little margin for error—or bad weather or bad luck, for that matter. Entire families are just a severe thunderstorm or a day’s illness away from disaster.

Social protection plans help ease that stress by giving people a wider margin. Every person is guaranteed at least a minimum amount of support. Social protection is designed to mitigate risks that are beyond the control of any one individual. It can take many forms — a minimum wage, a child labor law, a cash transfer to families who send their children to school or bring them for well-child visits.

Our research in the Institute supports FAO’s argument that strengthening social protection programs is one of the best ways to reach the poorest people in a society. Anything that keeps people who are already on the margins from falling into utter destitution functions as social protection. Social protection plans were a vital lifeline for poor people during the global food price crisis of 2007-2008; such plans have also worked well during other, more contained shocks such as crop failure. Many low-income countries have found that providing basic benefits is not beyond their means. Put simply, social protection is an affordable way to give people more “say” in what happens to them.

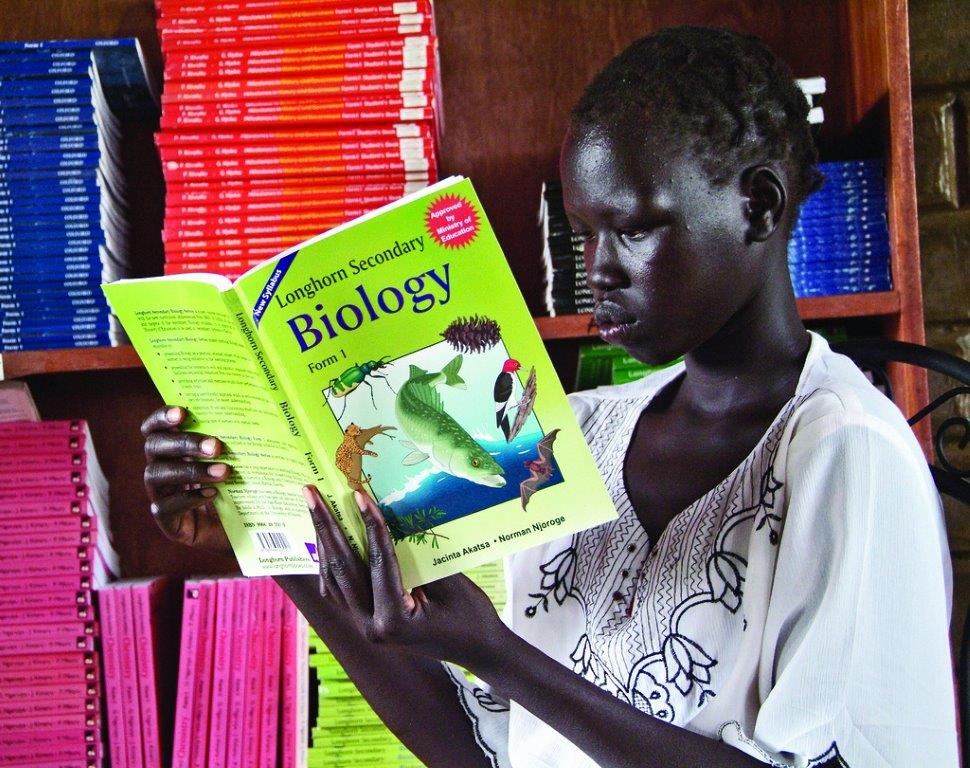

Poverty is one barrier to being able to plan for the future. Two others reinforce each other: lack of education and gender discrimination. As a hunger organization, Bread for the World Institute has argued (particularly in our 2015 Hunger Report, When Women Flourish… We Can End Hunger), that even beyond the inherent importance of education and gender equality, the world will not be able to end hunger without the full participation and empowerment of everyone, male and female.

Too often, girls are forced into marriage rather than being sent to secondary school. Child marriage is not only a serious human rights violation in itself, but, as detailed in CARE’s new report Vows of Poverty, a wedding “vow” at age 13, or 14, or 15, generally means a lifetime trapped in poverty. Why? Because it takes away a person’s right to make decisions and prevents her from acquiring the knowledge needed to make the best decisions for her situation.

Vows of Poverty lists 26 countries where girls under 18 are more likely to be married than in school. The juxtaposed numbers vary in severity, from a difference of 4 percent in Tanzania (37 percent of girls are married and 33 percent are in school) to a high of 66 percent in Niger (76 percent of girls are married, 10 percent are in school). But there has been progress. According to Girls Not Brides, a global consortium of more than 500 civil society organizations, child marriage gained unprecedented attention in 2014, with a record number of governments expressing support for ending it.

The millions of underage girls who are already married should not be forgotten. Marriage generally means the end of a girl’s education, but this is not inevitable. CARE’s TESLA project in Ethiopia, for example, works with married girls and often their husbands as well, showing how couples can communicate and work together to improve their lives. Some married girls have returned to school, and some husbands, particularly those who are young themselves, have become open to taking on nontraditional responsibilities. Married girls participating in TESLA captured images of some of these changes: husbands and mothers-in-law helping to look after children so that young wives can study, or a young husband pleased that he has learned to bake injera, Ethiopia’s traditional bread.

Social protection, secondary education, and reserving marriage for adults give people more meaningful options for their futures. And armed with these, people can often accomplish much more than an onlooker might expect. Happy World Food Day!

Michele Learner is the associate editor at Bread for the World Institute.

Photo: Girls with secondary education, such as this teenager in Sudan, are better equipped to help themselves, their communities, and their countries. Margaret W. Nea for Bread for the World.