Editor’s note: This is the first of several blog posts that will appear on Bread Blog ahead of the official November 23 launch of 2016 Hunger Report: The Nourishing Effect.

By Todd Post, Bread for the World Institute

The late Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan once said, “Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not to his own facts.” I am reminded of those words whenever I talk to or read the words of someone who doubts that hunger exists in the United States. People may have their opinions on the subject, but thanks to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s annual report, Household Food Security in the United States, I have the facts — and you can, too.

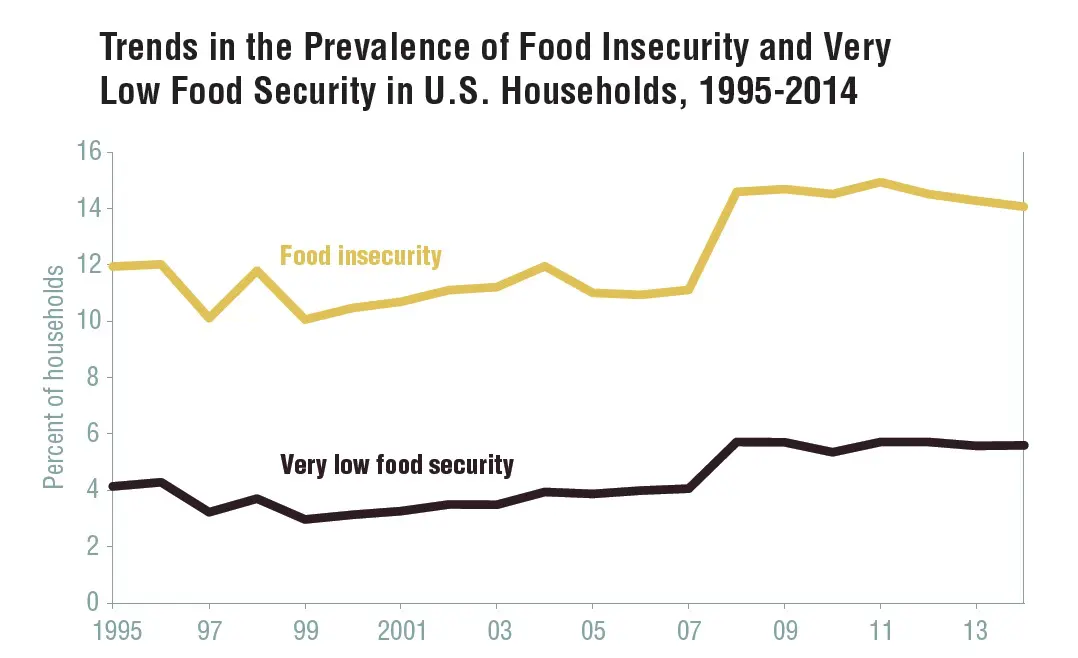

Ever since 2008, the number of food-insecure people in the country has hovered between 48 and 50 million. Since 2000, the number has never been lower than 30 million. Most Americans do not know there are this many people in the United States who struggle at times to get enough food to keep from going hungry. For that is what food insecurity means on a practical level. And at this point, we’re not even talking yet about the quality of the food and the compromises people have to make on nutrition to afford a sufficient quantity.

2015 marks the 20th anniversary of Household Food Security in the United States. It would be hard to overstate how important this publication is to us at Bread for the World and Bread for the World Institute. Household Food Security in the United States is the most authoritative source of information on the state of domestic hunger and food insecurity. Without the evidence presented in the report, I have no doubt Bread for the World would have had a much harder time defending the federal nutrition programs from the proposed cuts they’ve faced in recent years.

Data are collected by the Census Bureau as part of its annual survey and then handed over to USDA for analysis. Tens of thousands of households from across the nation are surveyed. They answer questions such as, “In the last 12 months, were you ever hungry but didn’t eat because there wasn’t enough money for food?” The survey includes up to 18 questions for households with children, and 12 questions for households without children.

Based on their responses, households fall into two categories: food-secure or food-insecure. The terminology becomes fuzzier once we start delving into levels of food insecurity. According to USDA’s nomenclature, food-insecure households can either be experiencing “low food security” or “very low food security.”

The concept of food insecurity is so wonky that it would not be obvious to an untrained ear that what we’re talking about is hunger. But as the survey question above demonstrates, there is no other way to ask people who are technically food insecure what they are experiencing — the term hunger must be used.

The terms “low food security” and “very low food security” used to be called, respectively, “food insecurity without hunger” and “food insecurity with hunger.” About 10 years ago, the National Academies of Science recommended that USDA stop using the term hunger in its reporting. The switch is a subject worthy of a blog of its own, but for now, let’s just say this is a fine example of what George Orwell meant in his essay “Politics and the English Language.”

In the 1980s, there were people in powerful positions of government stating publicly that they didn’t believe anyone in our country was hungry. Regardless of what was in plain view, there was no official data to contradict them. These statements were made against a backdrop of steep cuts to safety-net programs, wide-scale deinstitutionalization of people with mental illnesses and a concurrent rise in homelessness, and a tremendous explosion in the size of the food-banking network. Advocates for people affected by hunger responded by petitioning Congress to require the use of an instrument that counts hungry people. It took more than a decade, but that instrument became the food-security survey. As the statisticians say, the instrument has been validated and the information reported deemed reliable. Thus, there is no question: We have hungry people in the United States.

Household Food Security in the United States proved to be a crucial resource to me in my work on Bread for the World Institute’s 2016 Hunger Report. The report is about the bi-directional relationship between hunger and health. The Nourishing Effect: Ending Hunger, Improving Health, Reducing Inequality will be released November 23, the Monday before Thanksgiving. Research from around the world tells us that hunger and food insecurity make people more vulnerable to a range of health problems, from diabetes to hypertension to certain cancers and more. To say we have a hunger crisis, which is documented by those numbers — tens of millions of food-insecure people, year in and year out — is basically to say we have a public health crisis. I’ll explore this and other ideas in the 2016 Hunger Report in upcoming blogs as the report’s launch approaches.

Todd Post is senior researcher, writer, and editor at Bread for the World Institute.