Editor’s note: This post is part of a weekly series on fragility and hunger, rooted in themes from the 2017 Hunger Report: Fragile Environments, Resilient Communities.

By Derek Schwabe

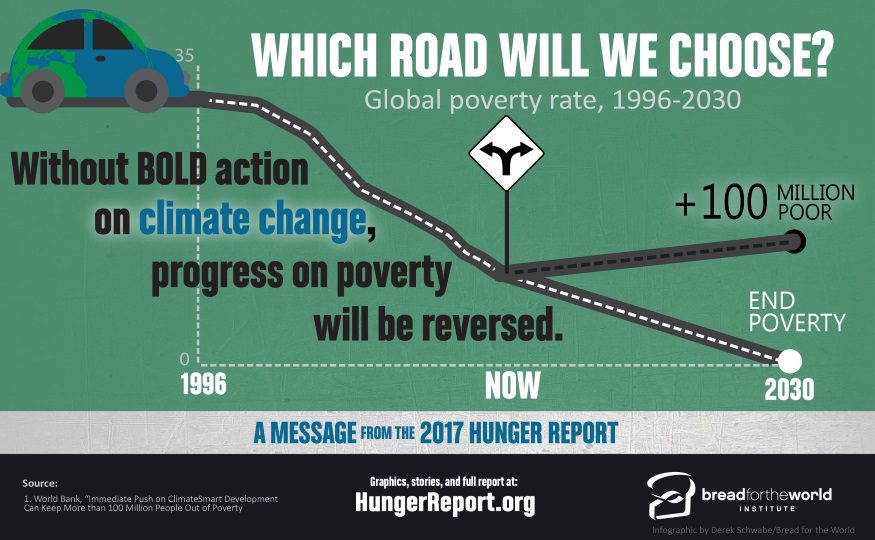

The world has made incredible progress against hunger and poverty over the past few decades, but climate change has started to unravel it.

Since 1990, more people have escaped poverty worldwide than during any other period in human history. The global poverty rate in 2015 was less than half of its 1990 rate. But as the 2017 Hunger Report warns, maintaining this progress means that governments — particularly the governments of the major emissions-producing countries — must reduce carbon emissions and curb rising surface temperatures. At least 100 million people will be pushed back into poverty by 2030 unless the world makes and follows through on commitments bold enough to change the current climate change trajectory.

More frequent and severe flooding, heat waves, droughts, and other extreme weather events will continue to upend food systems and rob whole populations of their homes and livelihoods. Temperature increases are altering global weather patterns, resulting in drastic reductions in crop yields. If climate change worsens while the human population increases, food shortages will be almost inevitable. Conflicts over scarce resources, particularly in fragile states, could escalate to full-scale wars.

Because of the potential for climate change to destabilize countries in some of the most volatile regions of the world, the U.S. military considers it a threat to national security.

It’s never easy to get all the countries of the world to act decisively together — even when global peace and security hang in the balance. That’s why the Paris Climate Agreement of 2016 is such a stunning achievement — it is truly global, and it urges immediate action. In fact, 197 countries made firm commitments to make “nationally determined contributions.” These commitments do not yet add up to enough to keep the planet’s temperature increase under 2 degrees C., which climate scientists agree is the maximum possible increase before catastrophic consequences such as the surge in poverty and displacement of millions become inevitable. However, the agreement also requires countries to periodically reevaluate and strengthen their efforts. This promise to go beyond the original commitment is a second reason why the Paris agreement is the world’s best hope.

The agreement way well also be our last hope. As far as the planet’s health is concerned, it was reached in the 11th hour — almost too late to prevent wide scale calamity, no matter what actions countries take in the future. Humans have been contributing to climate change for more than a century, with most emissions produced by rich industrialized countries. The Paris agreement is likely our last chance to avoid the most devastating effects of human actions on the planet.

U.S. leadership is integral to the agreement’s success, particularly because it has added more greenhouse gasses to the atmosphere than any other country. However, the incoming Trump administration has alarmed observers by giving ample reason to doubt that it will even recognize the existence of climate change, let alone take the swift, decisive actions needed. Even beyond its moral indefensibility in light of the human costs, the president’s “America first” mentality is extremely short-sighted, prioritizing immediate profit over preventing the incalculable economic costs the United States will incur in a world destabilized by climate change. And these bills will be presented, not to grandchildren or some other future generation, but to this generation.

Our elected leaders cannot secure a more stable and prosperous United States and fulfill U.S. responsibilities to the rest of the world without taking action to reduce carbon emissions. Honoring the Paris Agreement is the best way to start.

Read more about the contribution of climate change to hunger and malnutrition in the 2017 Hunger Report: Fragile Environments, Resilient Communities.

Derek Schwabe is a research associate at Bread for the World Institute.