Editor’s note: This post is part of a weekly, year-long series called the Nourishing Effect. It explores how hunger affects health through the lens of the 2016 Hunger Report. The report is an annual publication of Bread for the World Institute.

By Bread for the World Institute Staff

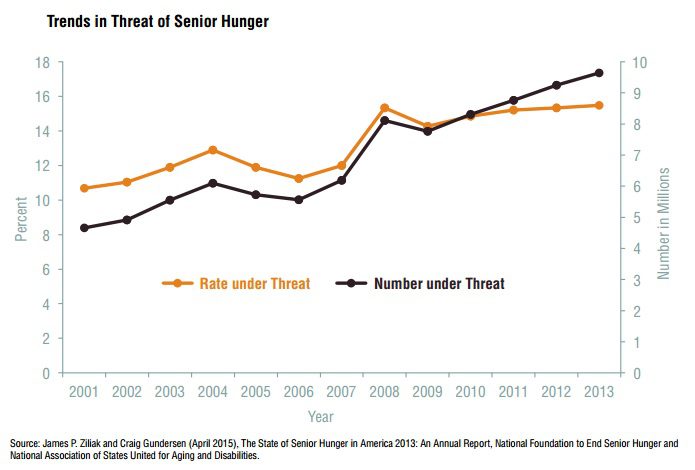

In 1960, one-third of all seniors lived in poverty, and two-thirds had no health insurance. Today, less than one-tenth live in poverty. Nearly all seniors qualify for Medicare, and 4.6 million low-income seniors are eligible for Medicaid as well. Social Security deserves the credit for much of this improvement. Although its retirement benefits are modest compared to public pension programs in other high-income countries, the senior poverty rate would be five times as high without them. That means that half of all seniors would be living in poverty today. Today, social welfare policies that worked to reduce economic hardship among seniors for the past half-century are coming under increasing stress. Between 2001 and 2013, the threat of hunger among seniors increased by 45 percent, according to James Ziliak and Craig Gundersen, in the most recent edition of the annual report The State of Senior Hunger in America. See graphic above.

Economic security in old age used to be described in terms of a three-legged stool: an employee pension, personal savings, and Social Security. The savings and pensions legs are wobblier than ever. For the most part, employee pensions have been replaced by 401(k)/IRA accounts. But the typical household with 401(k)/IRA holdings is projected to receive post-retirement monthly payments of less than $500 from these sources. Nearly one in five adults ages 55-64 has no retirement savings, according to a 2013 Federal Reserve survey. That leaves Social Security. For 20 percent of retired men and 30 percent of retired women, Social Security provides at least 90 percent of their total income.

The average Social Security benefit for men 65 and older is about $17,600 per year, and for women only $13,500. These seniors are over the poverty line, if not by much, but another complication is that as people get older, healthcare costs consume a greater share of their incomes. Thus, not surprisingly, the risk of food insecurity among older adults increases as medical expenses increase… Like heat or eat, “treat or eat” is an expression that speaks for itself. Cutting back on food to pay for medical treatment is clearly at odds with successful treatment of disease. Hunger and malnutrition are debilitating conditions at any age, but in older adults, 92 percent of whom have at least one chronic disease, hunger is potentially deadly.

SNAP participation rates among seniors are low: three out of five who qualify do not apply for SNAP…Nutrition programs, particularly SNAP, look like a bargain compared to the cost of a hospital stay. Among seniors eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid, an estimated 25 percent of hospitalizations are potentially preventable. People 65 years and older are hospitalized at much higher rates than younger adults or children. One in three seniors admitted to a hospital in the United States is malnourished. Malnourished patients have longer hospital stays and respond less well to treatment, their risk of developing surgical site infections is three times as high as those who are not malnourished, and 45 percent of the patients who fall while in the hospital are malnourished.

When a child or younger adult falls, the result may be nothing more than a bruise. But when seniors fall, they may break bones, and a fall may even prove fatal. The costs associated with falls during hospital stays amount to nearly $7 billion a year, and under the ACA, hospitals can no longer bill Medicare and Medicaid for the costs of treating conditions that were acquired in the hospital. Hospitals should make sure at discharge that patients are aware of available nutrition services and have access to healthy food. They have a financial as well as a moral incentive to do so.

This post has been adapted from Chapter 1 (pp. 61-67) of the 2016 Hunger Report: The Nourishing Effect. To read the full chapter, or find footnotes and sources, view the full report here.