By Derek Schwabe

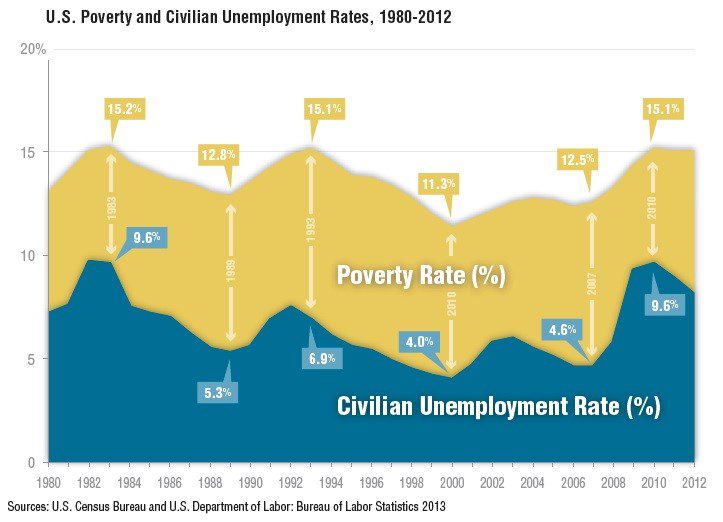

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the U.S. economy has finally achieved full employment, traditionally defined as below 5 percent. The unemployment rate for June 2016 was 4.9 percent, up a little from May’s even more impressive 4.7 percent. As we have pointed out before, full employment and lower poverty and hunger rates almost always coincide (see graphic above). Thus, reaching full employment is imperative to meeting the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of ending U.S. hunger by 2030, among the SDGs the United States and nearly every other nation adopted in September 2015.

In the 2014 Hunger Report, Ending Hunger in America, we anticipated that “a strong recovery capped by a return to full employment would improve U.S. food security levels by 25 percent.” Well, we’ve finally reached the full employment mark. What happened to food security levels? The percentage of American families that are food-insecure reached a high of 14.9 percent in 2011, in the wake of the Great Recession. By 2014 (the most recent year with complete data available), food insecurity had fallen by only 6 percent, to 14 percent of households. So where is that much-needed 25 percent improvement?

First, let’s not forget that the latest report on the food-insecurity rate is two years behind the latest report on the unemployment rate. The U.S. Department of Agriculture is slower than the Labor Bureau in reporting its numbers and does so only once a year using data that is already a year old. Significant economic growth over these two years is almost certain to have reduced the food-insecurity rate by at least a percentage point. If the food-insecurity rate falls to 13 percent in 2016 (a reasonable guess), that would be a 13 percent improvement, more than half of the 25 percent we had thought full employment would bring. But where is the other half? The reasons we haven’t seen it yet are complex and varied, but experts agree on four key factors. Policymakers have yet to take decisive action on any of them.

- Missing or discouraged workers: A frequent critique of the official unemployment rate is that it neglects to count those sometimes called “missing workers” – people who have given up looking for work, often after years of seeking and not finding a job. According to the Economic Policy Institute, if discouraged workers were counted, the current unemployment rate would be 6.4 percent. We can’t just pretend that these people and their families don’t exist. Many of them face hunger.

- Still-widening income inequality and low-wage jobs: Since 1979, hourly wages for the vast majority of American workers have either stagnated or declined – particularly during the period 2000 to 2011, which includes the Great Recession years. Over the same period, however, the incomes of the top 1 percent of earners rose by 153.6 percent. The federal minimum wage is still just $7.25 an hour. That’s only $15,080 a year for a full-time worker — nearly $4,000 below the poverty line for a family of three. Record numbers of workers – 28 percent in 2011 — are not paid enough to rise above the poverty line. Increasing the federal minimum wage is one of the most obvious, though far from sufficient, steps toward halting and beginning to reverse our country’s growing inequality.

- Wage discrimination: Discrimination translates directly into less grocery money. Equal pay for equal work is the law, but not the reality. Women are currently paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to a man for the same work. Thus, it’s not surprising that the majority of people in poverty are women. Wage discrimination based on race and ethnicity has shown no improvement since 1979. Black and Latino Americans still receive lower wages than whites for the same work – anywhere from 10 cents to 33 cents less for every dollar. As long as wage discrimination continues, women of all races and ethnicities, particularly African American and Latina women, and men from the African American and Latino communities will all receive lower pay and be at greater risk of hunger than white males. And, of course, people have virtually no power to change their gender, race, or ethnicity.

- The gutting of labor unions: The truth is that employers rarely if ever want to raise wages, because that cuts into profits. Even workers’ pointing out that they can’t feed their families has essentially failed to change this mindset. That’s why workers have historically relied on the collective bargaining power of labor unions to force employers to pay living wages. But U.S. unionization has fallen from a peak of 35 percent in the 1950s to a mere 6 percent in 2013. Without unions to stand up for them, workers are virtually defenseless in the face of wage stagnation or decline. They have little option but to accept the wage that is offered – which, for 28 percent of the entire U.S. workforce, is a poverty-level wage.

Full employment is still the first and most vital step toward ending hunger in the United States. But it must be “real” full employment – counting missing and discouraged workers. It’s time for the Bureau of Labor Statistics to revise its methodology so that it captures realistically the harsh realities that most American workers — especially low-income workers — face in the post-recession economy. And income inequality, low-wage jobs, discrimination, and the decline of unions will limit the impact of full employment on hunger unless and until Congress and the administration take decisive action.

Derek Schwabe is a research associate at Bread for the World Institute.